Excerpted from The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

By Ernie Suggs, photos by Natrice Miller/ AJC

Dan Moore Jr. and Kyler Winston-Kendricks had their routine down to a science. Moore Jr., the president and CEO of the APEX Museum, and Winston-Kendricks, his intern, were conducting a tour for 29 high school seniors from the Harley School in Rochester, New York.

The museum, founded by the late Dan Moore Sr., highlights Black history and culture. The students, mostly white, were on an educational trip to study Atlanta’s civil history, and just two hours after their plane landed Wednesday morning, they found themselves deep inside the APEX — Atlanta’s oldest Black history museum.

Moore Jr. and Winston-Kendricks took turns leading the group through hundreds of years of Black history. Beads of sweat rolled down Moore Jr.’s face as he told stories, occasionally slipping into an English or Portuguese accent. “People are seeking enlightenment,” Moore Jr. said. “They are seeking places where they can come and learn about Black history.”

When Moore Jr.’s father, Dan Moore Sr., arrived in Atlanta in 1974, the city itself was undergoing a rebirth. Maynard Jackson had just been sworn in as the first Black mayor of a major Southern city, and for Moore Sr., a minister-turned-filmmaker, Atlanta seemed like a place where Black stories could finally take center stage.

When Moore Jr.’s father, Dan Moore Sr., arrived in Atlanta in 1974, the city itself was undergoing a rebirth. Maynard Jackson had just been sworn in as the first Black mayor of a major Southern city, and for Moore Sr., a minister-turned-filmmaker, Atlanta seemed like a place where Black stories could finally take center stage.

Four years later, he transformed that vision into brick-and-mortar, founding the African American Panoramic Experience Museum on Ashby Street. By 1983, the museum had settled into an abandoned tire warehouse on Auburn Avenue, becoming a fixture in the city’s Black business and cultural corridor.

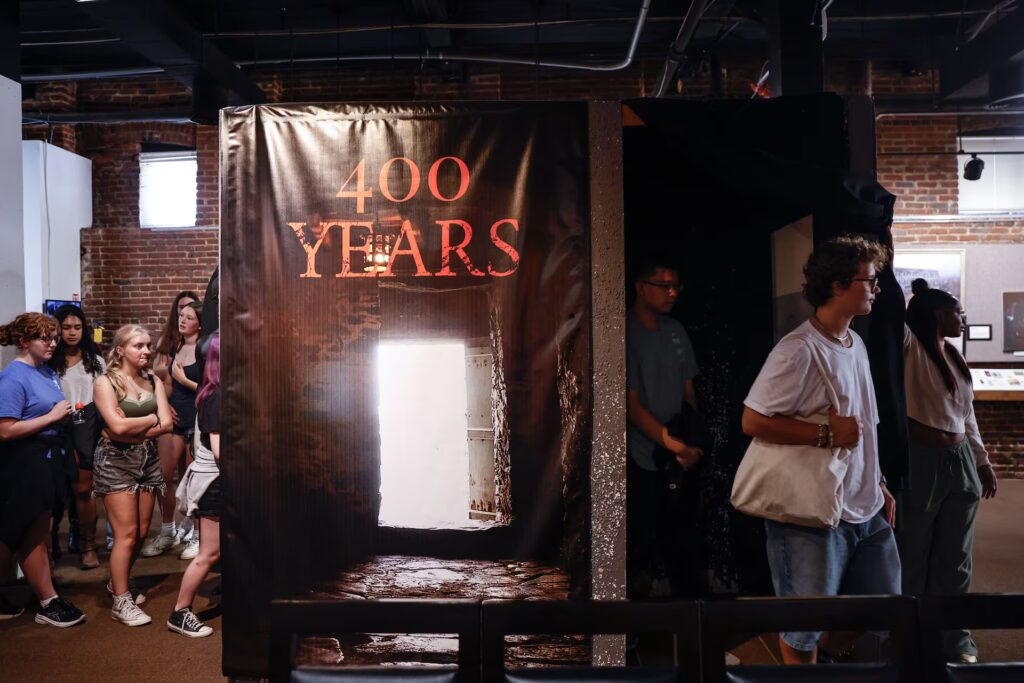

Through immersive exhibits — from the “Door of No Return” and replica slave ship to galleries celebrating Black entrepreneurship — the APEX became a place where history was told through the lens of those who lived it.

A century later, the man who built the APEX is gone. But his legacy is being reshaped by the one person who has known it longest — his son.

“It has been challenging, to say the least,” said Moore Jr., who took over after his father’s death in 2024. “I know that he was doing it for over 45, 46 years. I’ve only been at it for a year and some change — and I’m tired.”

As a child, Moore Jr., 67, sat on the floors of the museum’s first space on Ashby Street, playing with toys while his father met with figures like Benjamin Elijah Mays, the Morehouse College president who had urged Moore Sr. to use his filmmaking gifts to preserve Black history.

Now, the younger Moore is responsible for keeping that history alive and for ensuring the APEX remains relevant in an era of digital museums and short attention spans.

“There had been a kind of lack of communication as to what the APEX was doing in the community,” Moore Jr. said.

Then a close friend asked him a blunt question: In an era when Black museums and DEI programs are being attacked, and gleaming competition like the National Center for Civil and Human Rights — just a mile away — is undergoing a $57 million renovation, “Is the APEX still relevant?”

For Moore Jr., that question became his mission statement.

“The times have changed, so the museum may have to make some changes, too,” Moore Jr. said. “The narrative has never changed, but how we tell the story may have to change.”

Under his leadership, the museum has launched several efforts to modernize. A new APEX TV Network, available on Roku, is in development, along with traveling exhibitions and digital curriculum projects that connect the museum’s archive to classrooms and audiences worldwide.

The museum is also active on Facebook, TikTok and Instagram.

He’s doing it with the help of a young staff, led by 22-year-old Winston-Kendricks, an Africana Studies major at Georgia State University, who walks over to the museum every day to work for free. Everyone on the staff is a volunteer. Nobody — including Moore Jr. — draws a paycheck.

“My staff — most of them are in their early 20s — have a certain je ne sais quoi about them,” Moore Jr. said. “They have a knack for pulling things together and just making it happen. They have no fear.”

Winston-Kendricks, who calls her work at APEX “spiritual,” says the museum has become an extension of her own research and identity.

“I’ve always felt a connection with history. Growing up, I was a museum fanatic. My mom always took me to museums,” Winston-Kendricks said. “I have two aunts who have master’s degrees in history. I was always into learning something that wasn’t taught in schools.”

Her passion for history runs deep through her own family lineage. She recently discovered that her fourth great-grandmother was among the first enslaved Africans sent from Georgia to Liberia in the 1830s under the American Colonization Society’s controversial “Back to Africa” movement, where more than 13,000 African Americans were relocated to the West African colony.

But the settlers, who were born in the United States, had never seen Africa and struggled to adapt to the unfamiliar environment.

They faced tribal conflicts, malaria, yellow fever and other tropical diseases.

“They were begging to come back to Georgia to work on the plantation as slaves instead of being free,” Winston-Kendricks said. “So eventually, she somehow came back. She became a slave again.”

She repeats that story to the Harley School students who listen quietly.

Marissa DeSiena, head of the Upper School at the Harley School, said watching her students respond to the tour in real time was powerful.

“They really brought the history alive,” she said. “It didn’t feel like history. It was a lived experience that continues to be lived today. Their delivery was so riveting that it engaged students in ways they would not otherwise be engaged.”

Moore Jr.’s approach to leadership differs from his father’s tireless, around-the-clock devotion. Moore Sr. would work in the museum 12 hours a day, leading tours, securing funds and refreshing exhibits. Then he would go home and work on ideas for the next day.

“Unlike my father, I’m not here 24/7,” Moore Jr. said. “I’m a little different — at the end of the day, I shut things off. I value other parts of my life to make sure I can make this happen.”

That balance, he believes, is essential to sustainability — both his own and the museum’s.

While the original APEX remains a modest 7,500-square-foot space, Moore Jr. is looking beyond its walls. His father once dreamed of a 90,000-square-foot complex, complete with a 20-foot pyramid and robotic exhibits — “like Epcot, but for our story.”

Moore Jr. wants to revive that vision.

“We’re not in a capital campaign yet, but we’re building relationships — not just in Atlanta, but even outside the United States and in Africa,” he said.

In the meantime, the museum is sustaining itself through small fundraisers and community events — from a Black-perspective celebration of America’s 250th anniversary to a November fundraiser.

The museum once averaged about 62,000 visitors a year. Moore Jr. said attendance has already climbed to 85,000 this year, fueled, he believes, by both a backlash against attacks on Black museums and a renewed social media push. DeSiena said she discovered the museum through national education listservs.

Skipping away from the tour for a while, Moore Jr. ducked into a storage room and pulled out a few containers holding artifacts — old dolls, vintage curling irons, an wooden golf club, an old restaurant menu from a place called Coon Chicken Inn and a spelling bee trophy awarded by The Atlanta Journal to the city’s best speller from Atlanta’s “colored schools.”

“I’ve always had a dream to make sure my father’s dream was met,” he said. “Whether it would be me or part of the team, it didn’t matter as long as that vision got met.”

For now, his goal is simple: to make sure the APEX continues to tell the stories his father fought to preserve and to ensure that future generations will see themselves reflected on its walls.

“The APEX is still here,” Moore Jr. said. “And we’re still relevant.”

Full article: https://www.uatl.com/news/2025/10/dan-moore-jr-keeps-his-fathers-apex-legacy-alive/